Background

About six months ago, I got assigned a task to write a convention-driven documentation generator at work. Our first thought was to use Wyam for this, but after discussions with Dave Glick, he lured us into trying a new shiny project he was working on called Statiq. Creating a new site with Wyam at that point would've resulted in a rewrite once Statiq was released since it would make Wyam obsolete.

We started out with Statiq, and for someone with almost zero-experience with Wyam, the learning-curve was steep. The lack of documentation for Statiq at that time resulted in lots of chatting with Dave and lots of source code reading. The result, however, turned out great. We did lots of cool stuff like generating tables and pages from SQL queries, downloading artifacts from Azure DevOps, and generating documentation from the assemblies, integrating Swagger UI for API documentation, etc. For me, Wyam has always been magic that I never really grasped, but Statiq on the other hand was easy to work with once you got the hang of it.

So, what is Statiq?

Statiq is the world's most powerful static generation platform, allowing you to use or create a static generator that's exactly what you need.

Seems compelling, right? Additionally, since Statiq runs on .NET, you will have all the power of .NET in your static generator pipelines. This is what really makes it shine!

How Statiq works

(The following section is copied from the official Statiq documentation and reflects the state of Statiq by the time this blog post was written)

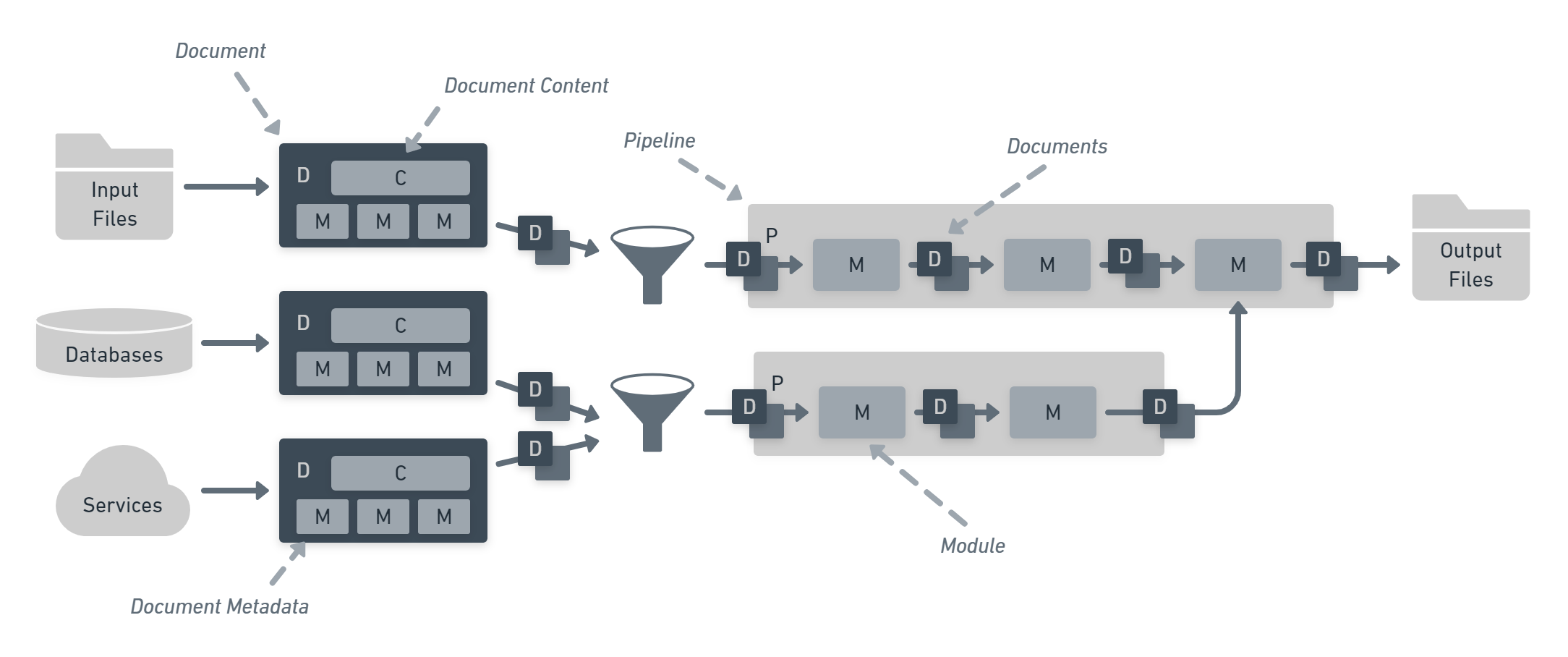

Statiq is powerful because it combines a few simple building blocks that can be rearranged and used in limitless combinations. Think of it like LEGO® for static generation.

- Content and data can come from a variety of sources including input files, databases, and services.

- Documents are created which each contain content and metadata.

- The documents are processed by pipelines.

- Each pipeline consists of one or more modules that manipulate the documents given to it by transforming, aggregating, filtering, or producing entirely new documents.

- The final output of each pipeline is made available to other pipeline and may be written to output files or deployed to hosting services.

Motivation

Back in December, when the documentation generator I was working on became feature complete, I wanted to continue using Statiq as it continued to evolve. This was when I decided my next project would be porting this blog to use Statiq. The old Wyam template I was using worked, but it was something I copy-pasted from Gary Park's blog and I had almost zero knowledge on what happens behind the scenes. As with most software developers, I don't trust magic and need to know how stuff works. Therefore, it was decided my next project would be porting this blog to Statiq.

TODO: Rewrite my blog with @statiqdev and then blog about it. I've had the privilege to work with the framework for a work thingy and I see great potential in it. Wyam was pure magic to me, but Statiq I can understand 😀

— Martin Björkström (@bjorkstromm) December 4, 2019

Attempt 1 - Porting the Wyam Blog recipe to Statiq

My first thought was to port the old Wyam blog recipe and theme to Statiq, so I cloned the Wyam sources and started porting these to Statiq.

After a couple of hours working on this, which can be found here, I quickly realized that this is very difficult and time consuming. And worst of all, I was porting code which I had no idea of what it was doing. The Wyam blog recipe was very extensible and I did not need many of the extension points it was offering. Some of the code would also have been better off just re-written in Statiq. Once again, I consulted Dave...

Attempt 2 - Using Statiq.Web

Once Dave was happy with Statiq Framework, which is the core of Statiq, he started working on a replacement for the Wyam recipes, namely Statiq Web and Statiq Docs. So at the beginning of March I decided to give Statiq Web a go (source code here). I quickly faced the same problems with that as with Attempt 1. While the recipe was partially ported, it still lacked themes, which led me into porting the old Wyam themes to Statiq. The result would have been much like using Wyam, i.e. magic which I did not understand :) So I wanted full control...

Attempt 3 - Using Statiq.Framework

As I had used Statiq Framework previously for work related stuff, I was quite comfortable with this approach. I started by contributing a Handlebars module to Statiq, because I prefer using Handlebars over Razor for simple templates. Once the Handlebars module was pulled in, I started porting my blog. The first thing I did was to take the HTML output from the old Wyam-powered blog and create handlebars templates from it. The next step was to create some pipelines. The basics of the pipelines are described in the following sections. To better understand the concept of Statiq pipelines and phases, please read Statiq's offical documentation. The full source for the pipelines that create my blog can be found on GitHub.

Blog post pipeline

The main pipeline in my blog engine is the pipeline that handles the blog posts. It reads all blog posts, using the ./posts/*.md glob pattern in the input phase. The process phase extracts metadata from Front Matter (the small YAML section on top of the document), renders markdown to HTML, generates an excerpt, and lastly changes the destination extension to .html. We'll skip the post process phase for now and go straight to the output phase which basically just writes the processed documents to disk.

public BlogPostPipeline()

{

InputModules = new ModuleList

{

new ReadFiles("./posts/*.md")

};

ProcessModules = new ModuleList

{

new ExtractFrontMatter(new ParseYaml()),

new RenderMarkdown()

.UseExtensions(),

new GenerateExcerpt(),

new SetDestination(".html")

};

...

OutputModules = new ModuleList

{

new WriteFiles()

};

}

Tags pipeline

Every blog post contains a list of tags, defined in the Front Matter. These tags are displayed on the various pages, including the post itself, the index page (which shows the top-ten tags), and the tags page which list all tags. For each tag, the site also has a page which lists all blog posts tagged with the specific tag (see e.g. .NET). The tags pipeline creates the tag documents which is used on the various pages and which results in the separate tag pages. In order to get the tags from the blog posts, we specify that this pipeline has a dependency on the blog post pipeline. This will instruct Statiq to execute the process phase of the blog post pipeline before executing the process phase of the tags pipeline and make the blog posts available inside the process phase.

The input phase reads a single document, which is the handlebars layout for our individual tag pages. The process phase will merge the single document from the input phase with the blog posts from the blog post pipeline grouped by tags. This basically gives us one document per tag (e.g. .NET, Azure, etc.) which contains the blog posts as child documents. All documents will have the content of the layout, _tag.hbs, which we read in the input phase. After that we will set the destination of the output document to match the tag name, specified in the metadata with key GroupKey, and additionally sanitize the filename to make it URL-friendly. Last, but not least, we will render the handlebars template as specified in the content of the document by passing it a custom model that we create for each document. If we had used Razor as out template language instead of Handlebars, we could have moved the logic to the templates. I prefer logic-less templates; thus, we need to prepare the model before passing it to the template engine.

public TagsPipeline()

{

Dependencies.Add(nameof(BlogPostPipeline));

InputModules = new ModuleList

{

new ReadFiles("_tag.hbs")

};

ProcessModules = new ModuleList

{

new MergeDocuments

{

new ReplaceDocuments(nameof(BlogPostPipeline)),

new GroupDocuments("Tags")

}.Reverse(),

new SetDestination(Config.FromDocument(doc => new NormalizedPath($"./tags/{doc.GetString(Keys.GroupKey)}.html"))),

new OptimizeFileName(),

new RenderHandlebars()

.WithModel(Config.FromDocument((doc, context) => new

{

title = doc.GetString(Keys.GroupKey),

posts = doc.GetChildren()

.OrderByDescending(x => x.GetDateTime(FeedKeys.Published))

.Select(x => x.AsPost(context)),

tags = context.Inputs

.OrderByDescending(x => x.GetChildren().Count)

.ThenBy(x => x.GetString(Keys.GroupKey))

.Take(10)

.Select(x => x.AsTag(context)),

}))

};

OutputModules = new ModuleList

{

new WriteFiles()

};

}

Tag Index Pipeline

The page that lists all tags is called the tag index and is generated using the tag index pipeline. This pipeline has a dependency on the tags pipeline in order to get all the tags. The input phase reads the template for the tag index and the process phase just sets the correct destination for the document before rendering the template. The model for the rendered document reads all tags from the tag pipeline.

public TagIndexPipeline()

{

Dependencies.Add(nameof(TagsPipeline));

InputModules = new ModuleList

{

new ReadFiles("_tagIndex.hbs")

};

ProcessModules = new ModuleList

{

new SetDestination(Config.FromValue(new NormalizedPath("./tags/index.html"))),

new RenderHandlebars()

.WithModel(Config.FromContext(context => new

{

tags = context.Outputs.FromPipeline(nameof(TagsPipeline))

.OrderByDescending(x => x.GetChildren().Count)

.ThenBy(x => x.GetString(Keys.GroupKey))

.Select(x => x.AsTag(context)),

}))

};

OutputModules = new ModuleList

{

new WriteFiles()

};

}

Archive pipeline

The archive page that shows all blog posts grouped by year is generated using the archive pipeline. This pipeline has a dependency on the blog post pipeline and basically works the same way as the tag index pipeline. We read the template in the input phase and sets a destination and render the template in the process phase.

public ArchivePipeline()

{

Dependencies.Add(nameof(BlogPostPipeline));

InputModules = new ModuleList

{

new ReadFiles("_archive.hbs")

};

ProcessModules = new ModuleList

{

new SetDestination(Config.FromValue(new NormalizedPath("./posts/index.html"))),

new RenderHandlebars()

.WithModel(Config.FromContext(context => new

{

groups = context.Outputs.FromPipeline(nameof(BlogPostPipeline))

.GroupBy(x => x.GetDateTime(FeedKeys.Published).Year)

.OrderByDescending(x => x.Key)

.Select(group => new

{

key = group.Key,

posts = group

.OrderByDescending(x => x.GetDateTime(FeedKeys.Published))

.Select(x => x.AsPost(context)),

})

}))

};

OutputModules = new ModuleList

{

new WriteFiles()

};

}

Index pipeline

The index page has a similar pipeline as the archive and tag index. It has a dependency on both the blog post pipeline and the tag pipeline in order to list the blog posts and list the top-ten tags. The construction of the model used for rendering the template is a little more complex than the other pipelines, but apart from that they are similar.

public IndexPipeline()

{

Dependencies.AddRange(nameof(BlogPostPipeline), nameof(TagsPipeline));

InputModules = new ModuleList

{

new ReadFiles("_index.hbs")

};

ProcessModules = new ModuleList

{

new ExtractFrontMatter(new ParseYaml()),

new SetDestination(Config.FromValue(new NormalizedPath("./index.html"))),

new RenderHandlebars()

.WithModel(Config.FromDocument((doc, context) => new

{

description = context.Settings.GetString(FeedKeys.Description),

intro = doc.GetString("intro"),

posts = context.Outputs.FromPipeline(nameof(BlogPostPipeline))

.OrderByDescending(x => x.GetDateTime(FeedKeys.Published))

.Take(3)

.Select(x => x.AsPost(context)),

olderPosts = context.Outputs.FromPipeline(nameof(BlogPostPipeline))

.OrderByDescending(x => x.GetDateTime(FeedKeys.Published))

.Skip(3)

.Select(x => x.AsPost(context)),

tags = context.Outputs.FromPipeline(nameof(TagsPipeline))

.OrderByDescending(x => x.GetChildren().Count)

.ThenBy(x => x.GetString(Keys.GroupKey))

.Take(10)

.Select(x => x.AsTag(context)),

socialMediaLinks = doc

.GetChildren("socialMediaLinks")

.Select(x => x.AsDynamic())

}))

};

OutputModules = new ModuleList

{

new WriteFiles()

};

}

Feeds pipeline

All blogs need to provide a syndication feed and Statiq has great built-in support for this. The Feeds pipeline generates both RSS and Atom feeds using the GenerateFeeds module. The content for the feeds comes from the documents in the blog post pipeline, which the feeds pipeline depends on.

public FeedsPipeline()

{

Dependencies.Add(nameof(BlogPostPipeline));

ProcessModules = new ModuleList

{

new ConcatDocuments(nameof(BlogPostPipeline)),

new OrderDocuments(Config.FromDocument((x => x.GetDateTime(FeedKeys.Published))))

.Descending(),

new GenerateFeeds()

};

OutputModules = new ModuleList

{

new WriteFiles()

};

}

Assets pipeline

This is a simple, isolated pipeline for just copying assets (css, js, images, etc) from the input directory to the output directory.

public AssetsPipeline()

{

Isolated = true;

ProcessModules = new ModuleList

{

new CopyFiles("./assets/{css,fonts,js,images}/**/*", "*.{png,ico,webmanifest}")

};

}

Layout pipelines

The shared layout, containing e.g. header, footer, and menu, for all the pages are created using two pipelines. The layout pipeline reads all handlebars templates where the filename does not begin with an underscore. This way we can separate the individual templates (e.g. for tags, tag index, archive, etc.) with the shared templates. The shared templates may also include metadata in the Front Matter, specifying whether it's a partial template.

public LayoutPipeline()

{

InputModules = new ModuleList

{

new ReadFiles("{!_,}*.hbs")

};

ProcessModules = new ModuleList

{

new ExtractFrontMatter(new ParseYaml())

};

}

The rendering of the shared template happens in the post process phase in an abstract pipeline called ApplyLayoutPipeline. In order to apply the layout to any document, we just need to inherit ApplyLayoutPipeline in our pipelines and the shared layout will be applied automatically.

protected ApplyLayoutPipeline()

{

PostProcessModules = new ModuleList

{

new SetMetadata("template", Config.FromContext(async ctx => await ctx.Outputs

.FromPipeline(nameof(LayoutPipeline))

.First(x => x.Source.FileName == "layout.hbs")

.GetContentStringAsync())),

new RenderHandlebars("template")

.Configure(async (context, document, handlebars) =>

{

foreach (var partial in context.Outputs

.FromPipeline(nameof(LayoutPipeline)).WhereContainsKey("partial"))

{

handlebars.RegisterTemplate(

partial.GetString("partial"),

await partial.GetContentStringAsync());

}

}).WithModel(Config.FromDocument(async (doc, ctx) => new

{

title = doc.GetString(Keys.Title),

body = await doc.GetContentStringAsync(),

link = ctx.GetLink(doc),

year = ctx.Settings.GetString(FeedKeys.Copyright)

})),

new SetContent(Config.FromDocument(x => x.GetString("template")))

};

}

The post process phase, which is a powerful concept of Statiq, is a phase executed in parallel for each pipeline where you will get access to all documents from all non-isolated pipeline. This can be used to get the tags displayed on the blog posts without creating a circular dependency. In order to get the tags from the tags pipeline into the blog posts, we pre-pend the modules in the post process phase with some additional modules which renders a template adding some metadata including the tags from the tags pipeline. This is important because we want the tags to be clickable, with links, taking us to the tag page.

public BlogPostPipeline()

{

...

PostProcessModules = PostProcessModules.Prepend(

new SetMetadata("template",

Config.FromContext(async ctx =>

await ctx.FileSystem.GetInputFile("_post.hbs").ReadAllTextAsync())),

new RenderHandlebars("template")

.WithModel(Config.FromDocument(async (doc, context) => new

{

title = doc.GetString(Keys.Title),

date = doc.GetDateTime(FeedKeys.Published).ToLongDateString(),

body = await doc.GetContentStringAsync(),

tags = doc.GetList<string>("tags")

.OrderBy(x => x)

.Select(x => context.Outputs

.FromPipeline(nameof(TagsPipeline))

.First(tag => tag.GetString(Keys.GroupKey) == x))

.Select(x => x.AsTag(context))

})),

new SetContent(Config.FromDocument(x => x.GetString("template"))));

...

}

Summary

If you've made it this far, congratulations! Now you hopefully know a little bit more about how Statiq works and the concept of pipelines, modules, and documents. For me, the biggest aha moment when starting out with Statiq came when I realized that documents are just placeholders for metadata. Documents may or may not contain content, but they will always contain some metadata. Documents may or may not exist in the input directory, and the may or may not be written to the output directory, but they will always contain metadata.

Please note, that if your only intention is to create a blog, or port your existing Wyam-based blog to Statiq, this approach may not be what you want. You should consider waiting for Statiq Web to be released, and you'll get the same (or even better) experience that you can get with Wyam today. But if you're like me and like tinkering then I definitely recommend creating your own site just using the modules found in Statiq Framework. It's also very easy to create custom modules yourself, even though this post does not contain any information about that. But stay tuned, who knows, maybe I will write a post about custom modules or shortcodes in the future.

A special thanks goes out to Dave Glick for all the effort you put into this wonderful framework and the countless hours of support. Wyam is dead, long live Statiq!